The state senator had an appointment out of town, and all his colleagues knew it. As soon as he left, the other political party, exploiting its temporary one-seat advantage, rushed to the floor a new legislative district map, though the state had adopted a compromise following the decennial census nine months before. The new map, the other party believed, would assure it a solid majority beyond the decade. The senate passed it, on party lines, in 30 minutes.

Situational ethics: Who’s right? Was there a wrong?

The story is real. The senator was Henry L. Marsh, a Democrat in Richmond. Marsh’s appointment was in Washington, at Barack Obama’s second inauguration. The Virginia Senate was split 20-20, and the previous April it had hashed out a Senate map with Republican Governor Bob McDonnell. The elected attorney general, Republican Ken Cuccinelli, set to back the new plan, was gearing up to run for governor. Amid the uproar, however, the House speaker, Republican William J. Howell, killed the proposal on a parliamentary maneuver. Said Howell, “I am committed to upholding the honor and traditions of both the office of speaker, the institution as a whole and the Commonwealth of Virginia.”

Gerrymandering also has a long tradition, but its increasingly aggressive use, thanks to computer-generated voter data, is distorting our elections, diminishing our representation, discouraging voting, and feeding legislative gridlock. It is an opportunity to jam the other side in this 50-50 political era – not the cause but rather an effect of growing intolerance of views and priorities with which we, any of us, disagree.

State legislatures are splitting cities, towns, even voting precincts to maximize party control. The state houses in Raleigh, Columbus, Harrisburg and Tallahassee contend for the title; Richmond also shows prowess for the increasingly purple Commonwealth of Virginia.

The Democrat won the past two presidential and four U.S. Senate elections in the Old Dominion. Democrats swept statewide posts (governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general) in 2013, breaking a 40-year streak in which the White House’s party lost the governor’s mansion the following year.

In the Virginia Senate, Republicans hold a 21-19 majority (after a 2014 special election in which Democrats lost a seat). That slender divide may be a fair representation of the whole state – it’s hard to say, since Virginia voters do not register by party. But in the House of Delegates, the GOP has a 67-32 majority (with one independent). The U.S. House delegation is Republican, 8-3. What’s going on here?

First, a trend. The New Deal Coalition, in which rural whites tended to be Democrats, is (literally) dead. In Virginia as in some other states, many of their children left for the cities; those that remain tend to vote Republican.

Second, the Great Sorting. Democratic majorities tend to be concentrated in cities and close-in suburbs; they are dark blue. Exurbs and rural areas tend to be pink, though on two-color maps they are red. It’s challenging to spread Democratic voters beyond geographically compact districts. But as legislators know, the same skill they have applied to splitting precincts could be applied to creating representative maps.

Thus the third factor: gerrymandering. Of course partisans want to win, and the Constitution imposes few limits on redistricting. But gerrymandering counters the spirit of the Framers, who sought to counter what Madison called, in Federalist No. 10, the “mortal disease” of faction:

“Complaints are everywhere heard . . . that the public good is disregarded in the conflicts of rival parties, and that measures are too often decided, not according to the rules of justice and the rights of the minor party, but by the superior force of an interested and overbearing majority.”

What does an “overbearing majority” look like? Virginia’s Senate caper. And its House of Delegates elections.

In 2013, 52 of the 100 House winners were either unopposed or had no major-party opponent; another 23 won with at least 60 percent of the vote. Thus voters in three-fourths of the districts had no real choice. And they get it: Voter turnout in state elections (which is easy to measure, as elections occur in odd-numbered years, opposite federal) has declined by half over the past 30 years.

An advisory ethics panel appointed by Democratic Governor Terry McAuliffe issued recommendations in December, among them a non-partisan commission created under a constitutional amendment to draw state and congressional districts. The ethics panel, chaired by former Democratic congressman Rick Boucher and former Republican lieutenant governor Bill Bolling (who was presiding when the GOP pulled its Senate maneuver), explained its reasoning:

“When politicians choose who[m] they will represent, rather than being chosen by their constituents, that decision is based predominantly on personal political preservation and enhancing the number of districts represented by the party that controls the redistricting process. Gerrymandering is a self-evident conflict of interests, inherently undemocratic and a disservice to the communities and people of the Commonwealth.”

Speaker Howell dismissed the proposal. His House has declined to act on similar bills.

Meanwhile, the General Assembly’s 2012 map of the state’s congressional districts was found in violation of federal voting rights law. A federal district court determined that the map packed black voters into the Third District, reducing their influence in adjacent districts and diminishing minority representation overall. The Assembly was ordered to draw a new map this year.

The state House and Senate maps, with 100 and 40 districts, are hard to decipher. The U.S. House map, with 11 districts, is easy. What’s with the 5th, stretching its middle finger from North Carolina to Loudoun County, 175 miles north? Or the 10th, which runs from the toniest suburbs of Washington over several Appalachian ridges to West Virginia?

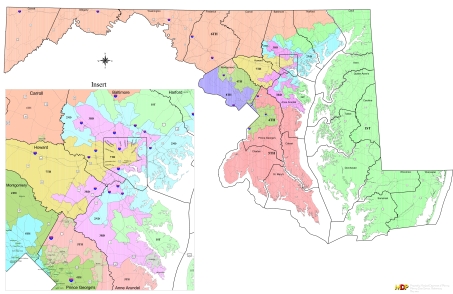

I whack on Virginia because I’ve resided in it for 50 years. Of course the GOP isn’t alone. Across the Potomac, the overwhelmingly Democratic legislature in Annapolis produced a near mirror of Virginia’s 10th in Maryland’s 6th District, in hopes of picking off an incumbent Republican in 2012. (After Democrats targeted 10-term Rep. Roscoe Bartlett, some sniped at House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi for inviting the Republican to sit with her at the 2011 State of the Union Address.) The 6th, after the 2000 census, ran from West Virginia under the Pennsylvania border to the Susquehanna River. Ten years later, the Democrats sacrificed the competitive 1st District on the Eastern Shore, ensuring it would stay Republican, and drew the 6th deep into D.C.’s liberal suburbs. It worked. Maryland’s U.S. House delegation went from 6-2 Democratic to 7-1, at the expense of Democrats on the Eastern Shore and Republicans in the mountains.

Maryland’s 2002 congressional map. The 6th District is orange; the 1st is green. (Maryland Department of Planning)

In a polarized era, characterized by our disdain for those who think another way, gerrymandering is a weapon. Maryland’s voter registration is 68 percent Democratic – less than a U.S. House delegation of 6-2, much less than 7-1. (Despite party registration, Maryland elected a GOP governor in 2014 and 2002.) But the Virginia GOP’s lock on the state and federal lower houses distorts the commonwealth’s political complexion. It does not represent us.

Voters elsewhere are fighting back. In some states, including California and Florida, they have passed ballot initiatives affecting redistricting. Some have created appointed commissions to draw districts (like that recommended in Virginia). In Arizona, voters in 2000 passed an initiative to amend the state constitution to vest the drawing of congressional districts in an Independent Redistricting Commission (IRC).

The IRC drew the map in 2001. But after its second round in 2012, the legislature struck back, suing in federal court that the commission usurped the legislature’s authority under Article I section 4 (the Elections Clause): “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof.” The court upheld the commission: “In Arizona the lawmaking power plainly includes the power to enact laws through initiative, and thus the Elections Clause permits the establishment and use of the IRC.”

The Supreme Court accepted the legislature’s appeal on two questions: whether the Elections Clause and federal law permit Arizona to use a commission to map congressional districts, and whether the legislature has standing to bring the suit. Oral argument is scheduled for March 2.

According to the Brennan Center, the decision in Arizona Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission could invalidate congressional redistricting commissions in half a dozen states and also throw into doubt the tie-breaking procedures used in four states to resolve legislative deadlocks.

Let me get this straight. The Arizona legislature didn’t like the result of a ballot initiative, so it took its constituents to court. What do you think?