The martyrdom of Marcus Whitman, like the nobility of the Lost Cause, was taught to American school children for a century. The thumbnail of the story: The doctor/preacher convinced a president to safeguard Oregon for the United States rather than Britain, then was murdered by Cayuse Indian savages, who massacred him, his wife Narcissa and 11 other souls in 1847.

Facts. The Whitmans were young Calvinist missionaries from New York’s “burnt-over district,” origin of America’s Second Great Awakening in the early 19th century. In 1836 they joined fur traders on their spring trek over what became the Oregon Trail. Narcissa’s dispatches demonstrated to America that emigration to the West by wagon was possible for the fairer sex. In the wake of Andrew Jackson’s Panic of 1837 and growing competition from slave labor, White farmers were anxious to continue moving west.

The Cayuse, a tribe centered in the Walla Walla Valley of present-day Washington, gave the Whitmans land for a farm and mission and initially were curious about the preacher’s Calvinist ideas on heaven, hell and original sin. The Whitmans’ fellow travelers/proselytizers, Henry and Eliza Spalding, settled among the Nez Perce, along the Clearwater in present-day Idaho, across the Blue Mountains.

In the fall of 1842, Whitman left his wife (in the care of Hudson’s Bay Company factor John McLoughlin at Fort Vancouver, 250 miles down the Columbia) and crossed the continent. He stopped briefly in Washington before hurrying to Boston, there to convince the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, which had sponsored his faltering enterprise, to reverse its decision to cut off support. On his return in 1843, Whitman led a wagon train of emigrants from St. Louis to the Oregon Territory. By then, many Americans believed the fertile Willamette Valley (from which I buy most of my produce) was paradise. A growing stream of farmers made the trek. Their numbers helped convince the British that retaining claim to Oregon, jointly administered under an 1818 treaty, was impractical. In 1846 President James Polk and the crown peaceably settled the border at the 49th parallel.

The emigrants brought rounds of European diseases, especially measles, which killed perhaps 30 of 50 Cayuse in a nearby village in the fall of 1847. Dr. Whitman seemed able to cure White children, but the natives had no defense. Under Cayuse law, failed medicine men were executed, plus the Cayuse suspected Whitman was poisoning the victims. Whitman’s friends were expropriating Indian lands, and his brand of spirituality had long lost appeal. Tensions steadily rose on account of his operations and practices; Whitman never learned the native tongue, and the Whitmans ignored warnings to leave. On November 29, a band of Cayuse attacked the mission, at the time occupied by about 50 Oregon Trail emigrants, and killed the Whitmans.

After a kangaroo trial, five Cayuse were hanged in Oregon City in 1850. Rather than calm relations, the American system of justice whetted the emigrants’ appetite for slaughtering natives and stealing their land, abetted by the government’s custom of making treaties (in particular the Waiilatpu treaty of 1855) and then abrogating them.

Meanwhile Henry Spalding, not present at the massacre, invented a story about Whitman: His purpose in traveling east in 1842 had been to convince President John Tyler to obtain Oregon for the United States, and Whitman’s massacre was an element of a conspiracy between the Hudson’s Bay Company and Catholic priests to save the territory for Britain. (Never mind that the Hudson’s Bay Company had begun relocating to Vancouver Island in 1843 and in 1846 shuttered Fort Vancouver; Spalding’s hatred of Catholics fit the national mood.) Spalding refined his tale in succeeding decades. Picked up by The New York Times and others for whom the story served their own purposes, it became a chapter in history books and Manifest Destiny.

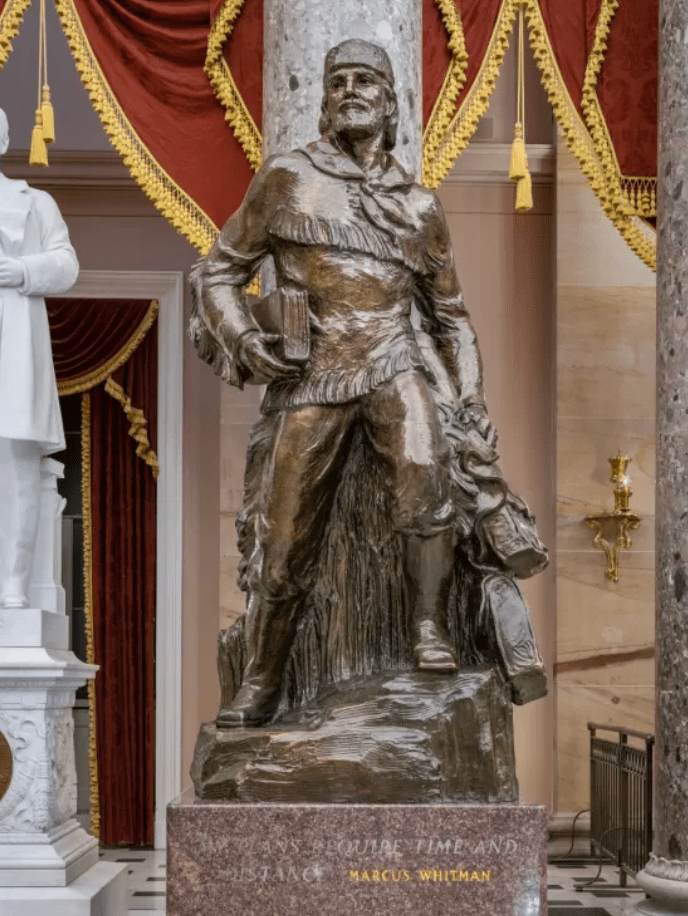

In Walla Walla, Stephen Penrose, president of Whitman College, knew the truth but exploited the myth’s fundraising potential. Locals saved the mission site, which in 1939 came under the National Park Service. In 1953 a bronze of Whitman was installed in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol; college alumnus and Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas gave the keynote, extolling the myth. The statue remains.

Blaine Harden, a former Washington Post reporter and native of eastern Washington, performed in an elementary school play about the Whitman story. In his 2021 narrative, Murder at the Mission, Harden writes that the doctor/preacher “had appeared in an opera, poems, hymns, children’s books, radio plays, movies, and the stained-glass windows of churches from Spokane to Seattle.” The myth survived correction of the historic record, developed in the 1890s by Chicago educator William I. Marshall, who dug into the archives of the American Board in Boston and of newspapers in the Oregon Territory (where Spalding was universally regarded as a liar). Eventually Whitman College relegated its heroic statue of Marcus Whitman to an obscure corner of the campus.

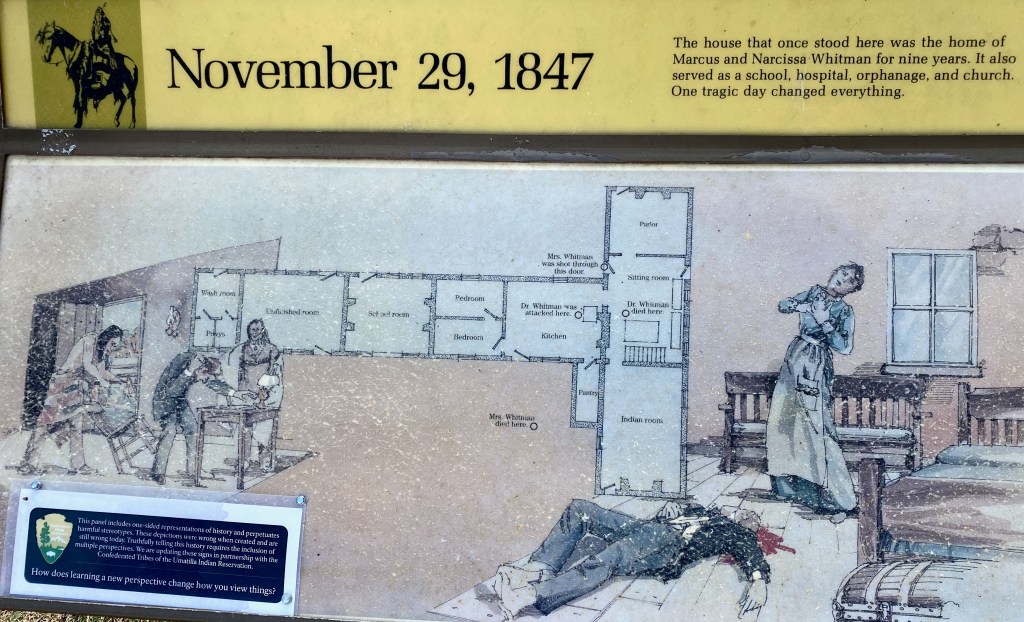

My aim in a tour of the Whitman Mission National Historic Site was to see whether the National Park Service has caught up with the facts. It is a work in progress. The 25-minute docudrama, produced in 2015, corrects the record. But on the mile-plus walk around the grounds, narrative panels erected in the 1970s remain. They tell the story from the perspective of the Whitmans and White emigrants, in the style familiar to Park Service narratives from coast to coast: line drawings of people and places accompanied by text. One panel depicts the moment the Whitmans were killed: Marcus lies in a pool of his own blood as Narcissa, fatally shot, clutches her breast. “One tragic day changed everything.”

A laminated placard attached to each panel reads:

This panel includes one-sided representations of history and perpetuates harmful stereotypes. These depictions were wrong when created and are still wrong today. Truthfully telling this history requires the inclusion of multiple perspectives. We are updating these signs in partnership with the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. How does learning a new perspective change how you view things?

We are in a moment that some of us, led by politicians like Ron DeSantis, would Whitewash our narratives. But history, like science, is a process of discovery.

We were not witnesses to the Whitman Mission. I appreciate the historical excavations that began 130 years ago, and the Cayuse and other tribes who contribute to my understanding of this nation’s founding. These narratives are there for anyone to consider—unless the Whitewashers succeed.

For example. A few miles from the mission site, on the grounds of the Walla Walla County Courthouse, a statue of Christopher Columbus is inscribed:

Italy’s illustrious son who gave to the world a continent. We shall be inclined to pronounce the voyage that led the way to this new world as the most epoch making event of all that have occurred since the birth of Christ.

Thanks for building this post!

LikeLike

>

LikeLike

I see how you’ve been engaging yourself while I vacation mindlessly.Nice! You often amaze me.

>

LikeLike