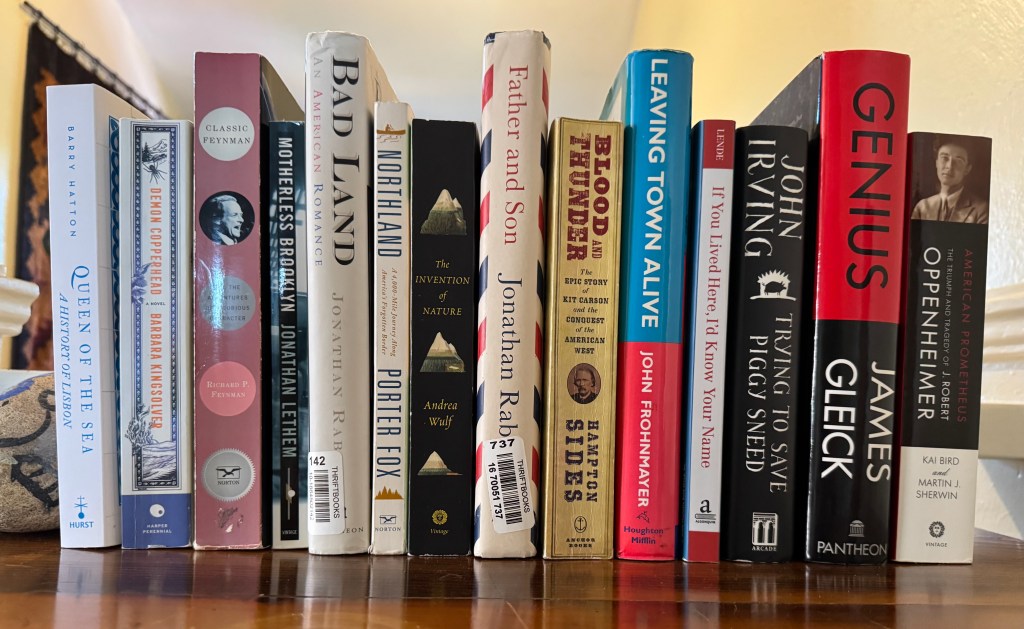

Some of my 2025 reading, whose theme was wandering through my shelves or used bookstores from Portland to Denton and places in between.

Kai Bird and Martin Sherman, American Promethius: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (2005). Sherman spent 25 years researching his subject; Bird assembled the notes into a readable Pulitzer-winning biography from birth to death. My reading revealed the mastery of Christopher Nolan in converting it into an Oscar-winning movie.

James Gleick, Genius (1992). The author reports that Oppenheimer believed Richard Feynman was the most valuable scientist on the Manhattan Project. I have no education in physics, so much of Feynman’s intuitive discoveries is over my head. The personal side of Feynman is terribly entertaining and led me to pick up another book (noted below) that’s a collection of his writings and university lectures, which were fully subscribed wherever he taught.

John Irving, Trying to Save Piggy Snead (1996). An anthology of short stories, essays and memories, among them an account of his invitation to dine in the White House with Ronald Reagan. Irving is a fan of neither Reagan’s aides nor his presidency. Of his decision not to visit the U.S. from his home in Toronto to promote his 16th novel, published in November, Irving told The New York Times: “I could not, would not, in good conscience go to my birth country, when there is such an authoritarian bully in the White House, and when the craven Republicans in the House and the U.S. Senate are complicit in their silence.”

John Frohnmeyer, Leaving Town Alive: Confessions of an Arts Warrior (1993). In a former life, I watched Frohnmeyer’s stewardship of the National Endowment of the Arts from Capitol Hill. His portrait of the George H.W. Bush White House jibes with mine: visionless. A lawyer from a prominent Oregon political family, Frohnmeyer became a fierce defender of the arts and the First Amendment through his battles with GOP demagogues whom I knew up close.

Heather Lende, If You Lived Here, I’d Know Your Name (2006). Engaging essays of an Alaska immigrant living in coastal Haynes, where she writes the local newspaper’s obituaries. If you were to consider moving to the Last Frontier, you should read her work. Note: If you have a serious medical problem, the closest hospital is Seattle.

Mary Means, Something Worth Saving (2025). At times excruciating memoir of a dear friend, recounting a lifelong journey toward healing from a tragic, if outwardly normal, childhood.

Hampton Sides, Blood and Thunder: The Epic Story of Kit Carson and the Conquest of the American West (2006). Even that elongated subtitle doesn’t capture the range of the story, part biography of the country’s most celebrated tracker, part narrative of the Mexican War and army’s subjugation and erasure of Native culture.

Jonathan Raban, Father and Son (2023). Raban has become one of my favorite nonfiction writers. This was his last book, alternating his observations of his partial recovery from a stroke with his research into his parents’ lives and marriage, focused on his father’s British Army service during the Second World War.

Andrea Wulf, The Invention of Nature (2015). The centennial of the birth of German naturalist Alexander Von Humboldt in 1869 was the cause of celebrations throughout the world including the United States. He was the most famous scientist of the 19th century, having proved the connection of all life in a single ecology. Von Humboldt spent five years traveling the Americas, at the end of which he met with President Jefferson and Secretary of State Madison. He was an inspiration for his friend Simon Bolivar; his prolific writing was the roadmap for Darwin’s journey to “The Origin of Species” and inspiring for the contemplations of Emerson and Thoreau.

Porter Fox, Northland (2018). The author spends a couple years traveling the U.S. border from Maine to the Pacific. Among his chapters: the French exploration headlined by La Salle; how it is that Americans speak English rather than French; the largely liquid border of Minnesota; and the exploration and marking of the 49th parallel.

Barry Hatton, The Portugese: A Modern History (2011). A British reporter for the Associated Press, longtime resident of Portugal, traces the nation from its founding through the Age of Discovery to the Salazar dictatorship that ended in a 1974 military coup, to its admission to the EU and the 2008 financial crisis. For the U.S., the pertinent history is that Salazar’s rule was characterized by the same aims as the Trump administration’s: an economic elite controlling a poorly educated underclass with no social safety net. For 50 years since, the Portuguese have sought to weave themselves into the European Union and its higher standards of education and development.

Jonathan Raban, Bad Land: An American Romance (1996). My fourth trip through the world of the author is about the settlement of eastern Montana primarily by Northern Europeans in the early 20th century. The gist is that it’s how American capitalism works: The government, having erased the Indians, gave away their land to white homesteaders, who were drawn to the arid prairie by the evocative and false advertising of railroad executives. The railroads needed passengers and their agricultural production to fund their expansion. Settlement was propelled by the “scientific” theory that growing populations west of the 100th meridian would create the rainfall needed to flourish. The homesteaders were suckers. Their children continued migrating west, settling in places like the Idaho panhandle, where distrust of the federal government is most intense. Think Timothy McVeigh, Ruby Ridge, Aryan Resistance and Ted Kaczynski.

Jonathan Lethem, Motherless Brooklyn (1999). A joy of the independent bookstore is that titles can jump into your hands. I wanted to read the novel Edward Norton shaped into the movie. The novel, set in contemporary New York, is a first-person account of wayward children and small-time crooks. Norton transformed it into the best movie of 2019, set decades earlier, about Robert Moses and the big-time crooks who made New York’s infrastructure what it is.

Ralph Leighton, editor, Classic Feynman: All the Adventures of a Curious Character (2008). All the words are Feynman’s, from the physicist’s prodigious output. Credit Leighton for arranging them into an entertaining memoir I didn’t want to put down.

Barbara Kingsolver, Demon Copperhead (2022). My only explanation for not having read every word she’s published is that I don’t read much fiction. Masterfully told tale of characters playing out what ails us—poverty, ignorance and government/corporate malevolence—set in the Appalachian toe of Virginia amid the unending opioid epidemic (one in eight babies is born addicted, Kingsolver reports in a December 22 NYT column). The last two pages left my soul agape. Barry Hatton, “Queen of the Sea: A History of Lisbon” (2018). We couldn’t find many books in the U.S. about Portugal. I bought this one at a bookstore in Lisbon and started it on our way home. It draws me back to the city, the second-oldest in Europe, where we spent a week in November less as tourists than as potential immigrants. On our next visit, I’d like to see the historical sites we largely bypassed as we focused on its vibe.