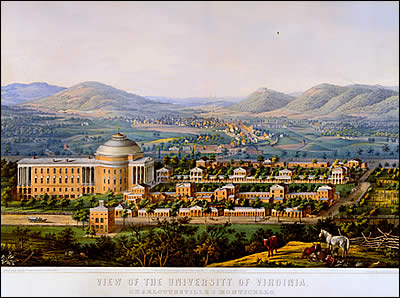

Recently I tossed decades of canceled paper checks, but one I kept: $424 for tuition and fees at the University of Virginia for fall 1978, my sophomore year. If college costs reflected CPI, this year Mr. Jefferson’s Academical Village would cost $1,552 per semester, as a dollar then is worth 36 cents today. Instead tuition now is $6,938/semester.

Recently I tossed decades of canceled paper checks, but one I kept: $424 for tuition and fees at the University of Virginia for fall 1978, my sophomore year. If college costs reflected CPI, this year Mr. Jefferson’s Academical Village would cost $1,552 per semester, as a dollar then is worth 36 cents today. Instead tuition now is $6,938/semester.

That check is on my home-office posterboard, along with the bill for my daughter’s recent tuition bill at a private university. Every parent with a college-age kid knows that the sticker price of private colleges is north of $50,000 per year, less scholarships for some. Financing college is an insurmountable burden for many.

Many issues are at play in these rising costs. One is the limited productivity gain for education: A teacher still stands in front of a given number of students to deliver a lecture/discussion. In the labor/capital relationship, the price of skilled labor has risen, and the price of money and capital-intensive goods has fallen sharply. (A color TV costs less today than it did a decade or four ago.) Critics of universities like to point their profligacy: fancy facilities, out-of-control football programs, superfluous research with little value for students.

The factor that interests me has little to do with economics or budgetary extravagance: it’s about choice. As costs have gone up, state government support to public colleges has fallen.

According to the American Council on Education (school presidents), inflation-adjusted tuition has surged about 250 percent at state four-year schools since 1980. The states in aggregate provided 60 percent of college budgets in 1975, and 34 percent in 2010. By another measure, state fiscal support in 2011 was equal to $6.30 per $1,000 of state personal income – down from $10.58 in 1976.

In Virginia, state support now amounts to less than 6 percent of my alma mater’s budget. (In what sense is that a state school?) In the past month, governors in Louisiana, Wisconsin and Illinois, among others, have proposed slashing state aid to higher education by hundreds of millions of dollars. During the Great Recession, between 2007–08 and 2012–13, California’s appropriations to its two public systems declined 30 percent, and per-student subsidies fell by more than half.

In Virginia, state support now amounts to less than 6 percent of my alma mater’s budget. (In what sense is that a state school?) In the past month, governors in Louisiana, Wisconsin and Illinois, among others, have proposed slashing state aid to higher education by hundreds of millions of dollars. During the Great Recession, between 2007–08 and 2012–13, California’s appropriations to its two public systems declined 30 percent, and per-student subsidies fell by more than half.

Another measure comes from the State Higher Education Executive Officers (the association of state boards of postsecondary education). In 1988 states provided $75 billion (in 2013 dollars) to post-secondary schools. In 2013 they provided $78 billion. That’s a 5 percent increase – despite a 56 percent increase in enrollment. Students’ net tuition payments over the same period rose from $19 billion to $62 billion, in 2013 dollars.

Much of that tuition is paid with borrowed money. Seven in 10 graduates in 2013 held debt, and that debt averaged $28,000, according to the non-profit Institute for College Access & Success. The New York Fed reported last month that total student debt nationwide stands at $2 trillion and that delinquencies (debt that has not had a payment made in 90+ days) are at 11.3% of outstanding debt.

The national price of college debt

The effect of starting one’s career with that kinds of debt?

- Debtors are more likely to “boomerang” to mom and dad’s basement and delay getting married, buying a home, and starting a family.

- They are less likely to start businesses.

- They are more likely to choose college courses and careers based on earning potential, rather than their passions.

Those who cannot or will not finance college by borrowing have limited options. Studies have proliferated about the hollowing out of the working class because of the loss over the same period of good-paying, non-college jobs to automation and offshore manufacturing. Family income and marriage rates have declined; out-of-wedlock births have increased. The difference a college education makes is incalculable. Almost.

We know that higher education benefits the individual (higher salary), private industry (lower training costs), government (higher income tax revenue), and society (higher standard of living). College-educated citizens have healthier lifestyles and are less likely to smoke or be obese. As parents they devote more time and energy to their children’s development. Higher education increases social mobility at a time when economic class divisions are sclerotic.

Higher education is also an investment in democracy. Half the population doesn’t vote – typically those who are less educated, have less income, and depend more on government social support programs. The reduction in public funding reflects a populace unwilling to shoulder the costs of educating its children.

As Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce reported in a 2011 study, the demand for college-educated workers – particularly those with backgrounds in STEM (science/technology/engineering/math) – has outpaced supply. The talent shortage limits the economic gains the nation would achieve as a whole. And it exacerbates the pay differential – income inequality – because employers must pay a premium for better educated workers.

In the 1960s young Americans were by far the best educated generation the world over. Today 42 percent of Americans age 25 to 34 have college degrees, way behind Korea and Canada, where more than half of the same age cohort have post-secondary credentials. According to the OECD:

The U.S. is the only country where attainment levels among those just entering the labor market (25-34 year-olds) do not exceed those about to leave the labor market (55-64 year-olds). This is why international comparisons look so different among younger age groups. Among 25-34 year-olds, the U.S. ranks 15th among 34 OECD countries in [post-secondary] attainment.

What has led us the precipice of a kind of national suicide?

Consequences of taxpayer choice

As with many social and economic indicators, we began contracting in about 1980. In 1978 California voters approved Proposition 13, amending the state constitution to limit property tax increases. That began a taxpayer revolt that other states imitated and that Ronald Reagan led as president. The Republican Party has advocated tax reductions and minimal social services ever since, and it now holds more seats in the U.S. House and state legislatures than at any time since the 1920s.

Thus it’s clear, at least among a majority who vote, that taxpayer-supported higher education is not a priority in many states. Our hostility to supporting higher education, through taxation, is undermining the resources we need to compete in the world and exacerbating inequality at home. (Though we do seem passionate about college football.)

Summarized Anthony P. Carnevale, co-author of the Georgetown report, “In recession and recovery, we remain fixated on the high school jobs that are lost and not coming back. We are hurtling into a future dominated by college-level jobs unprepared.”

Put another way, we have focused on what we don’t want – to pay taxes – rather than what we do want, which is, perhaps, to grow, enjoy abundance, support our children, and advance the nation that was bequeathed to us.

It’s a choice.

Pingback: A wake – or awake? – in Baltimore | Transformational Citizenship

I have some thoughts about this but not time to write the response I’d like to. Here is the gist of my argument, unrefined: Colleges receive gifts in staggering amounts (untaxed to the givers, you would quickly point out). I see campuses erecting new buildings and throwing away the old serviceable ones (even as they ask students to flush upward, and won’t offer trays to hold their $750 a month cafeteria food, so as to discourage “waste”) with those gifts, sometimes paying administrators phenomenal salaries, and generally using gifts to advance the school’s prestige, which then justifies further tuition increase. Where is the expectation, and the standard, of donors to colleges helping to increase accessibility even as they get their name plastered on a chair or wall? On the contrary, it seems these gifts seem to move schools toward higher costs for students as they build the school’s sense of “We are worth it because we have….” (new buildings, big names, superior athletics, etc).

You are suggesting that the taxpayers “make priority” the tuition at schools whose priority for their own students to access an education is questionable. I am so sick of hearing “85% of our students get aid”–when that aid might be a few percentage points of the annual cost of the school. I do not agree that the national commitment to college education (manifested in more $ sent straight to schools) should come before the colleges themselves seriously assess what they are doing with their resources–which seems to be pricing the middle class entirely out of the opportunity. When donors give (untaxed) gifts of thousands, even millions of dollars that don’t help, and may actually hurt, students’ ability to go to school, why should the public at large pick up the ever-increasing tab?

I don’t have data and links to show the contributions that colleges receive and how those contributions are spent, but as a “shopper” I would really like to know. I know that students from my “alma mater” call me every year, begging me to contribute to a scholarship fund, but every issue of the alumni magazine is bragging about new buildings going up and ever-fancier projects and institutes that seem to make the school look good.

I do not see anything in the college marketing materials, either to potential applicants or accepted students, explaining to me, the parent—invited to take out five-digit loans–that explains the school’s budget, income, resources, or spending priorities. We get an aid offer for one year, and attendance costs for one year, as if the costs of the next three–or, for public schools, more likely four–years is’t relevant.

LikeLike