Oregon’s polarized election results reflected those of other states but with the twists that typify the state’s distinctions, seen in four ballot questions as well as contests for office. From them I infer our political values and democratic health: we are split.

As a history student, I was most interested in a question the legislature referred to voters: “Amends Constitution: Removes language allowing slavery and involuntary servitude as punishment for crime.” Sitting at my dining table with a two-page ballot and the state’s book-length voters guide, I blackened the yes oval and moved on. But when the results came in, I thought: Where did this clause, similar to the Thirteenth Amendment, come from?

Ratified in 1865, it reads: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” The language of the amendment—and of Oregon’s 1857 territorial constitution—originated in the 1787 Northwest Ordinance, under which the Confederation Congress set rules for the admission of what became the five Great Lakes States. (The anti-slavery provision was proposed by Thomas Jefferson in the 1784 version of the Ordinance,[*] but the Congress removed it.) After Congress inserted the language into the Thirteenth Amendment, the former slave states found their loophole to rebuild their Peculiar Institution in another form: “involuntary servitude” as punishment for a growing list of crimes. Most of the nation has followed the model since.

A national campaign seeks to eliminate that loophole from the constitutions of 25 states. Colorado acted first, in 2018, when 66% of voters approved the clause: “There shall never be in this state either slavery or involuntary servitude.” Nebraska (68%) and Utah (80%) followed in 2020.

This year Vermont (89%) and Tennessee (80%) were decisive. In Alabama, 77% approved “no form of slavery shall exist in this state; and there shall not be any involuntary servitude” buried in a constitutional rewrite. Louisiana’s legislature watered down a similar proposal by making clear that “involuntary servitude” in its prison system was A-OK, and the original sponsors urged voters to reject it. They did.

In Oregon, the reform passed with 55%.

No campaign opposed the amendment, though the Oregon Sheriffs Association submitted a statement against it in the voters guide. “Oregon Sheriffs do not condone or support slavery and/or involuntary servitude in any form,” but the measure “creates unintended consequences for Oregon Jails that will result in the elimination of all reformative programs and increased costs to local jail operations.” The full statement, 300 words, contends that passage would invalidate prison work programs—an interpretation at odds with the legislative resolution (sponsored only by Democrats, opposed by 11 of 33 Republicans) that referred the question to the ballot. Lawyers suggest that requiring inmates to work for no pay may violate the prohibition of involuntary servitude, but little case law has developed.

Why was the margin so thin? Oregon barred slavery from its founding. Its White fathers, predominantly from border states, also forbade Black people, slave or free, to settle here. I have written of Oregon’s particular racism, which remains evident in myriad ways. Did opponents object to the removal of the slavery language, or to unpaid labor? Was it tied to “wokeness”? Did GOP legislators signal opposition? Or did some voters simply align the question with Portland liberals and a legislature they feel antagonizes them?

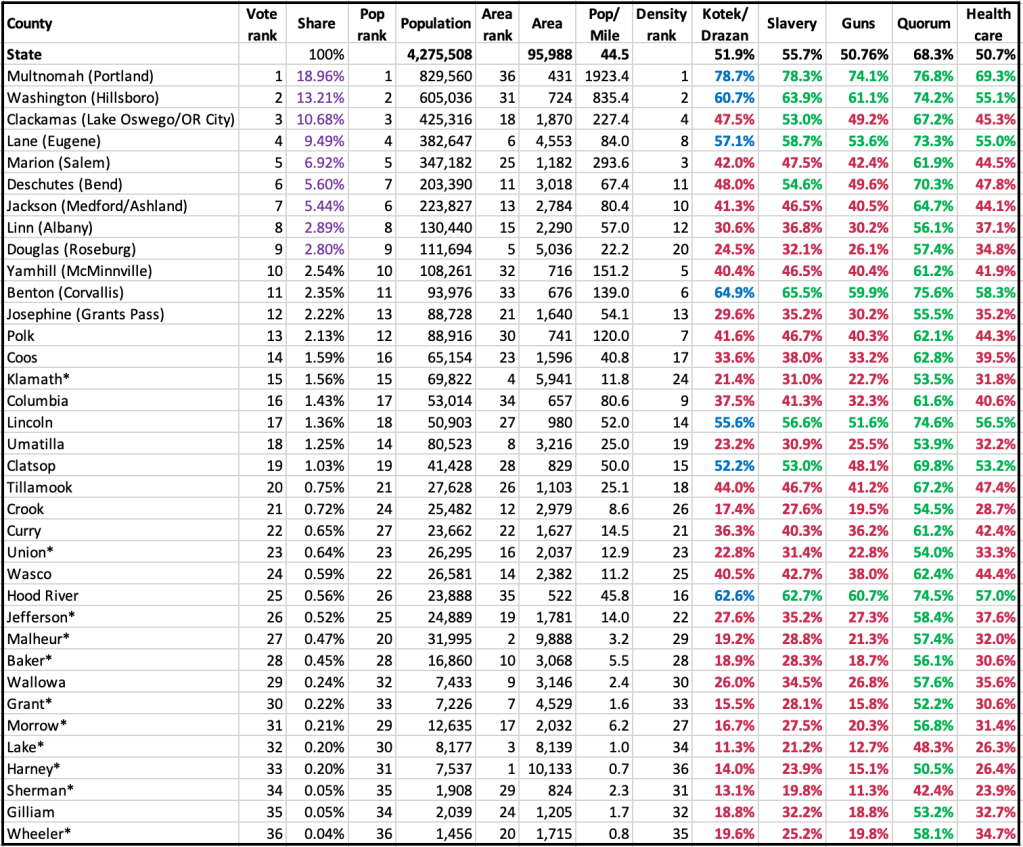

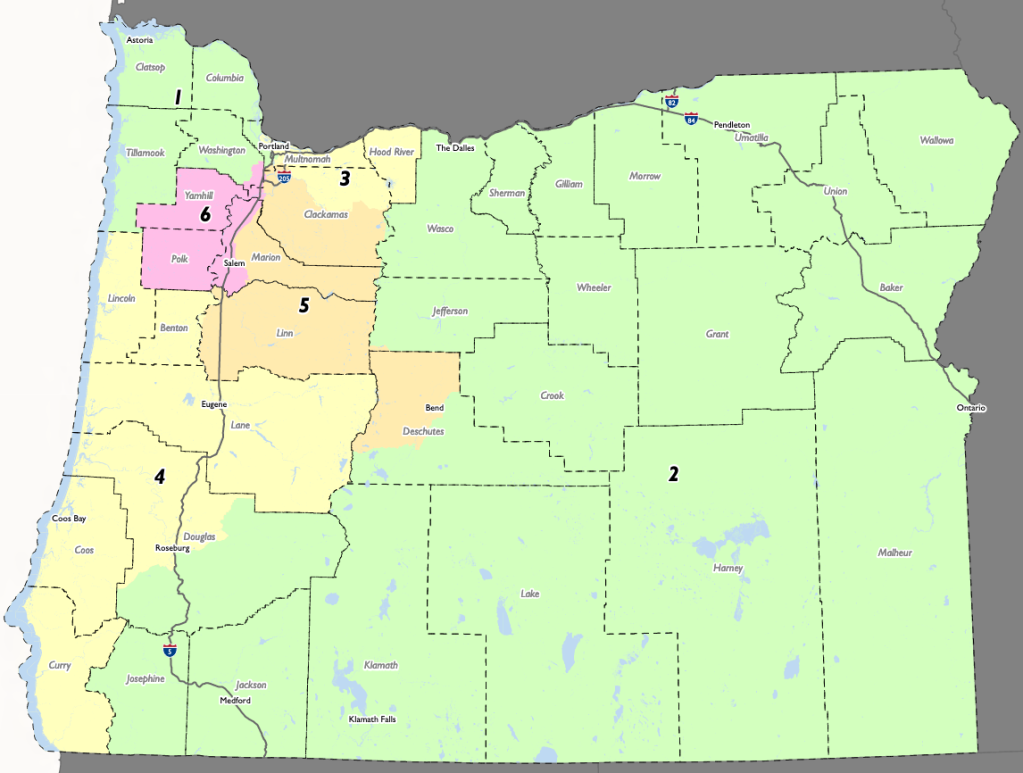

My table shows results for governor and the ballot questions in its 36 counties. (For governor, I calculated the voting shares of only Democrat Tina Kotek and Republican Christine Drazan, omitting counts for other candidates, including Betsy Johnson, a conservative former Democratic senator who ran as an independent and received 8.6%.) As in other states, differences between urban and rural were stark. The slavery question followed the vote for governor: Urban majorities voted overwhelmingly for Kotek and for “abolition.”

Ditto a petition initiative enacting a firearm permit process and outlawing magazines of more than 10 bullets, now among the strictest gun laws in the country. It passed with 50.7% statewide but was rejected by majorities in 30 counties. Several sheriffs have proclaimed that they won’t enforce it, the latest episode in a nationwide movement among elected sheriffs who assert they are judges as well as executives. (The law, effective 30 days after the election, is the subject of a challenge in federal court).

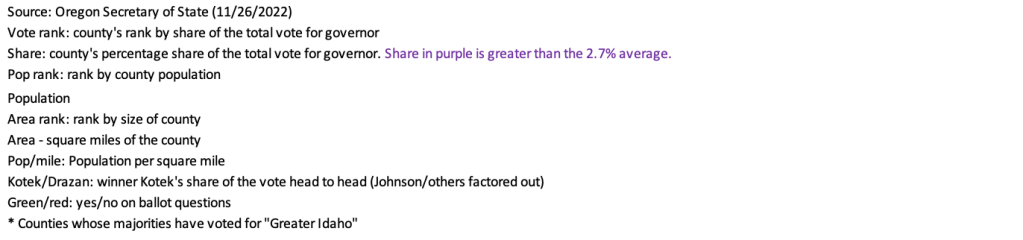

My pie chart illustrates that four counties account for 52% of the vote. Kotek drew 64% from those four. Twenty-five counties combined have less than the population of Multnomah (Portland). Fifteen have fewer than 15 people per square mile. The urban voters of metro Portland across three counties—plus fast-growing Bend, the university towns of Eugene and Corvallis and the resort communities in Lincoln and Hood River counties—comprise a solid if narrow Democratic majority.

Another perspective: The second congressional district, encompassing nearly three quarters of the state’s 96,000 square miles, has one-sixth of the population—about 706,000 people. By contrast, Multnomah, with 413 square miles, has 820,000.

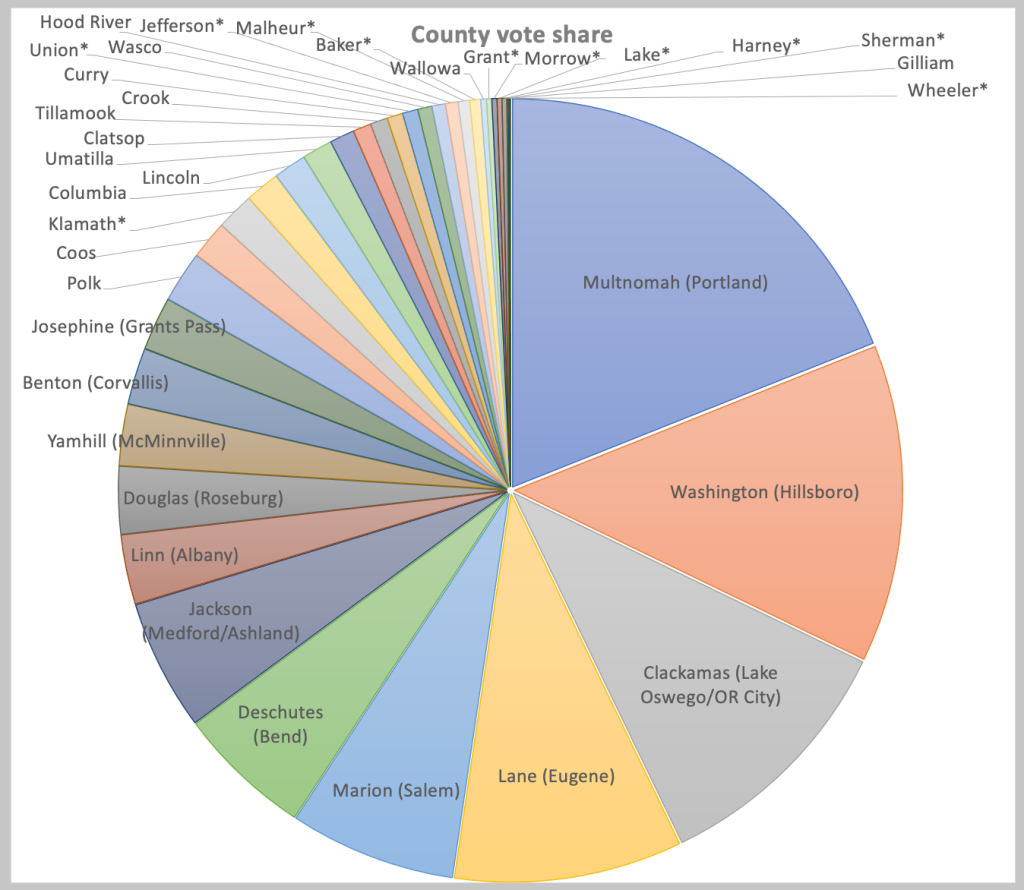

The second district’s estrangement from the Capitol in Salem has taken flight with a two-year-old campaign to secede from Oregon, the project of Mike McCarter and his “Citizens for Greater Idaho.” Majorities in 11 counties east of the Cascades (5% of the state’s population) have approved ballot measures calling on county commissions to talk about it (execution would require approval of the two state legislatures and Congress). Two counties did so in November. Three have rejected versions of the question—Douglas and Josephine in southwest and Wallowa in the northeast corner. A second try in Wallowa this year failed to gather required petition signatures.

Counter to the narrative, majorities in 34 counties, representing 99.75% of all voters, approved a constitutional amendment that disqualifies a legislator from running for reelection upon 10 “unexcused absences.” Organizers of the initiative were prompted by GOP walkouts that truncated legislative sessions three of the past four years; the quorum is two-thirds, rather than the simple majority almost everywhere else at every level of government. (Proponents opted against changing the quorum to simple majority—it didn’t poll well—but tossing legislators who don’t show up for work did.)

The fourth ballot proposal, referred by the legislature, adds to the constitution a directive that the state ensure access to “cost-effective, clinically appropriate and affordable health care as a right.” As I also favor motherhood and apple pie, I voted yes, as did 50.7% of my fellow citizens. Results matched those of the gun measure by virtually the same margins in the same counties.

For all four questions and the vote for governor, support correlated with population density. Harney is Oregon’s largest and least dense county. Voter support of all measures ranked near the bottom. A year ago its voters passed the Idaho initiative, 1,567 to 917. They don’t like much that’s happening in state government.

Oregon has had its civil conflicts. Harney encompasses the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, where separatists (White Nationalists? Right-wing terrorists?) occupied its headquarters complex in 2016 (only one of those indicted on federal conspiracy charges was a state resident). Proud Boys, many from Clackamas (and Washington State) made Portland a target of violence during the Trump presidency, and his administration deployed militarized federal agents to Portland against the summer 2020 Black Lives Matter protestors. The second district’s one-term representative, a mild-mannered lawyer with 12 years in the legislature, voted with the GOP’s election-denial caucus hours after rioters shit on the floor of the House. Cliff Bentz told his hometown newspaper, “I wanted people to understand they were being heard. These people are so angry about being left out.”

Its national reputation to the contrary, Oregon is not terribly liberal. Despite Democrats’ best efforts to gerrymander after the census, they will hold 58% of the seats in the 60-member House and 57% in the 30-member Senate—a working majority but short of the three-fifth margin required to raise taxes, much less the two-thirds quorum to stay in session. (I doubt the prospect of being disqualified from a $33,000/year job will affect the minority’s calculations on critical issues.) Democrats were greedy in redistricting the House of Representatives and ended up biting their nails over two seats and losing one, leaving their margin at 4-2, which is where they would have been with a fairer process.

On questions of values, which is what we call on government to answer, it’s unrealistic to expect a majority to moderate because a minority see issues through a mirror. Health care should be a right, and guns should be controlled, say a bare majority. (When I am awakened by gunfire across my street on Thanksgiving night, I want government to act.) Voting is how we answer divisive questions. Now and then, a minority takes up arms (see Nathaniel Bacon, Daniel Shays, the Whiskey Rebellion, the Confederacy).

Last year the Oregon Values and Beliefs Center polled Oregonians on the Idaho movement. By 43% to 34%, respondents thought the outcome would be negative for seceding counties (23% had no view). Two-thirds said secession was unlikely. Not surprisingly, a plurality of rural voters said counties should be able to secede (44% to 40%), and three in four Republicans agreed. A slightly narrower ratio of Democrats said the opposite.

My analysis focuses on urban/rural, using counties as the measure. But counties are arbitrary administrative units of the state. I could parse something else, such as educational attainment. Census data finds that in the first and third congressional districts, in which Portland predominates, 45% of residents have college degrees. In the second, 29%. The results at the ballot box, reflecting recent political realignment, are similar. Or view by party registration: Democrats 34%, Republicans 24%, unaffiliated/other 35%. Democrats have an edge, but only that.

As speaker of the Oregon House, Tina Kotek ruled with an iron hand. As governor by 3.5 percentage points, she has her political task cut out for her.

[*] Jefferson chaired a committee that proposed conditions for governments formed out of the Northwest Territory (west of Pennsylvania, north of the Ohio and east of the Mississippi rivers), among them: “That after the year 1800 of the Christian æra, there shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in any of the said states, otherwise than in punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted to have been personally guilty.” The clause was removed in deliberations of the Confederation Congress.