What have I learned in 60 years? Take little for granted, other than that I will (likely) return home from a bike ride.

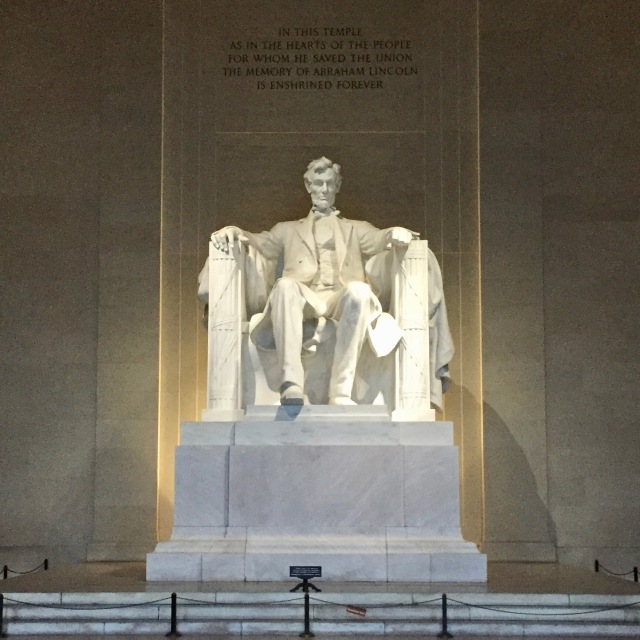

At dawn I took my customary solstice/birthday pilgrimage to the Lincoln Memorial and faced the Washington Monument, as I have done scores of times. On this occasion, I noted that I may never sit here again. In 20 days, I will fly away to a new hometown on the other coast. Though I will return to Arlington at least once, later in the summer, I have a glimpse of my own mortality: Everywhere I go in these three weeks may be for the last time. I feel neither wistful nor nostalgic, but grateful.

I turn and look at Abe, sitting on that chair. He took nothing for granted. Both of his great speeches – the greatest in our history – have at core propositions rather than assertions.

At Gettysburg, he said, we were engaged in a test of whether any nation conceived and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal could long endure.

Sixteen months later, in his Second Inaugural, he proposed that the Civil War was the price the nation paid for slavery. “Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.’”

These propositions apply to our moment, in which we are recycling the same conflicts we have experienced throughout our history. It’s no coincidence that the author of the Declaration Lincoln invoked was a slaveholder whose notions of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness became the American creed. John Calhoun, a two-term vice president under both parties, extrapolated from Jeffersonian philosophy the idea that states could nullify laws with which they disagreed – a justification for states’ rights used later to promote the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, a cause of the war a decade later, and for defiance of racial justice measures since.

What we face, now as then, is a conflict between Calhoun’s planter class and the interests of the whole. Throughout our history, the planter class – now as then backed by Northern bankers – has used fear of Other to draw support from white peasants who bleed for its wealth. Historian C. Vann Woodward (1908-1999) unspooled the myth of benevolent slaveholders, uncovering the violence and manipulation that drew in the peasants because, at least, they were not Negroes. That myth survived into the 1950s, wrote his protégé David Brion Davis, until Woodward “helped to reveal and reverse the fact that the South, despite its military defeat, had long been winning the ideological Civil War.”

That reversal, in my mind, ran from Harry Truman’s desegregation of the armed forces in 1948 (amid postwar prosperity) to the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. In the first half of that period, the nation embraced inclusion: the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts and the Immigration Act of 1965, which reversed exclusionary policies of the 1920s. At the end of the 60s, Neal Armstrong’s giant leap for mankind marked the peak of American power and prestige.

But over the next 11 years, we determined that Vietnam was a lie fomented by one president, faced the impeachment of another over anti-democratic corruption, experienced the vulnerability of the oil embargo, revolted over forced busing (race again, right in the middle), began to feel the effects of de-industrialization and foreign competition, and were humiliated by the Iran hostage crisis.

Enter Reagan, who said “government is the problem” and corralled the same forces of white grievance that Calhoun had organized in 1832. Their disaffection had always been cultural (anti-black), as Woodward explained. Reagan took advantage of the “malaise” of the 1970s to attack government and pursue wealth concentration in private hands: low taxes, deregulation, union-busting, and a Supreme Court that expanded the power of commerce at the expense of the government’s leavening hand.

We are now 30 years past Reagan. Seeing no help from the Democratic Party – decades ago a mix of racists and economic populists but now a multi-racial alliance led by educated urban elites – the next generation of Reagan Democrats is all in with Trump, who personifies its anger and grievance. As his followers’ primary news sources promote him and the planter class behind him, our polarization solidifies.

Donald Trump is the perfect manifestation of these disparate trends: a demagogue with overt racist appeal; a nationalist who views cooperation as weak; and a champion in all of his policies of powerful rent-seekers in legacy industries granted commercial advantages through the powers of the government held by all three branches.

As the Republican Party surrenders its heritage of open markets and (relatively) open borders to Trump’s whims, America again faces a test of its creed, not only whether a government of, by and for the people will perish, but whether it should survive. As Lincoln said, a house divided cannot stand.

I take nothing for granted. And I’m grateful I’m still here.

Brilliant. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike